The Chamberlain Effect: Why We Make Bad Decisions, Even When We Know Better.

On a cold, rainy night in 1962, Hershey, Pennsylvania, one of the greatest games in basketball history would take place. It’s the Philadelphia Warriors versus the New York Knicks.

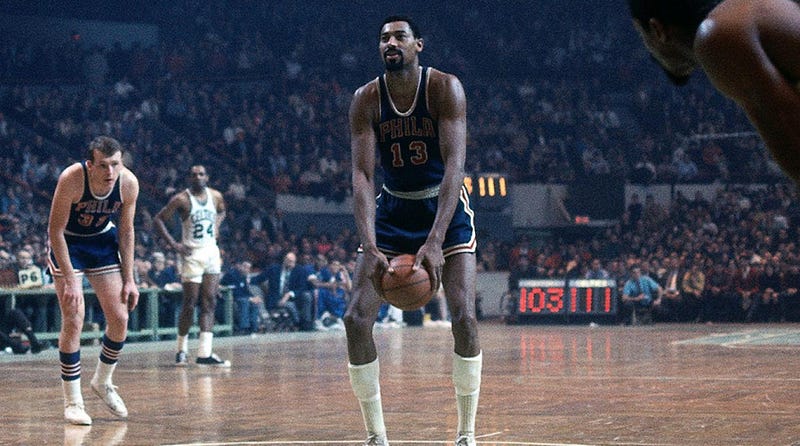

The star player of the Warriors was a 7 foot 1, 275 pound man with a towering physical presence. His name was Wilt Chamberlain.

In the game of basketball, 7 foot tall players look awkward and clumsy on the court. But Wilt Chamberlain was different. He was as tall as a giraffe and as graceful as a ballerina.

During the 1962 basketball season, Wilt Chamberlain averaged 50.36 points per game. A single season points record that has never been broken. In context, Michael Jordan, widely regarded as the greatest basketball player of all time, averaged 37.09 points per game in his best single season. Let that sink in for a second.

Back to the game. By the end of the first quarter, Chamberlain scored 23 points. 41 points at half time. 69 points in the third quarter. And boy, he wasn’t slowing down.

With 46 seconds left on the clock, Chamberlain broke free from five Knicks players, approached the basketball rim, jumped high and put the ball through the hoop. The arena exploded into a frenzy. Hundreds of spectators stormed the court, to celebrate and touch the hero of the night. Wilt Chamberlain had just scored 100 points, the most any player has ever scored in a professional basketball game.

But, that wasn’t all. Something strange occurred after this historic game. A head-scratching decision, some would say near insane, by the star man, Wilt Chamberlain.

Chamberlain’s puzzling decision, begs the question: why do we make bad decisions, or dumb choices, even when a good choice is right in front of our face?

Granny Shots and Free Throws

When Wilt Chamberlain first joined the NBA, he dominated his opponents physically, scoring at will, even when he was grappled by two or more players. But, when it came time to shoot a free throw — an unopposed attempt at scoring points — he was horrendous. We’re talking 40 percent of shots made from the free throw line.

At the start of the season leading up to the historic game, Wilt Chamberlain made a decision to try a different way of shooting free throws. Instead of shooting, like every other basketball player — overhand, releasing the ball near the forehead — Chamberlain switched to underhand free throws. Also known as the Granny Shot.

Throughout the season, Wilt Chamberlain would hold the ball between his legs, slightly crouch his knees and flick the ball upwards to the basket rim. And all of a sudden, he became a pretty good free throw shooter, netting close to 60 percent of his shots.

Then, on that historic night in Hershey, Pennsylvania, Chamberlain netted 28 out of his 32 shots from the free throw line. That’s an incredible 87.5 percent from the free throw line. The most free throws ever made during a single game of basketball in NBA history.

This drastic improvement, from 40 percent to 87.5 percent, didn’t occur because Chamberlain improved his athleticism or shooting skills. It happened because he changed the way he shot free throws. Wilt Chamberlain would stick by this good decision and improve as a free throw shooter.

Or would he?

After the historic game, something incredible happens. A baffling, near insane moment. Wilt Chamberlain stops shooting underhand, and reverts back to shooting overhand. He chose to go back to being a terrible free throw shooter!

There’s a saying that insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. Could insanity also be doing something different, finding a solution to your biggest problems and then, reverting back to your old ways that didn’t work?

There were no rational reasons for Wilt Chamberlain to stop shooting underhand free throws, as he wasn’t ignorant to the positive results of the new approach. But despite knowing better, Chamberlain switched back to his old way of shooting. And for the rest of his basketball career, remained a poor free throw shooter.

At that time, the only other player who shot underhand free throws was Rick Barry, a Hall of Famer, and just like Chamberlain, an unstoppable offensive juggernaut, who stood 6 foot 7 inches tall.

Unlike Wilt Chamberlain, Rick Barry never switched back to overhand free throws. And for a damn good reason. At the time of his retirement, Rick Barry held a godlike 90 percent free throw record, ranked first in NBA history. But, this could well have been Wilt Chamberlain’s record, if he had stuck to the underhand throw for the rest of his basketball career.

So, what’s it about the Wilt Chamberlain’s of the world — who make bad decisions even when they know better — that’s different from the Rick Barry’s of the world, who stick to good decisions, even when they’re an anomaly?

The Threshold Model of Collective Behavior

In a famous essay published over four decades ago, Stanford University sociologist, Mark Granovetter, tried to answer the question of why people do things out of a character. [3]

Granovetter used riots as one of the main examples. Because during a riot, otherwise normal people, get involved in destructive and violent behavior. Why would law-abiding citizens suddenly throw rocks through windows?

Before Granovetter’s paper, sociologists tried to explain this phenomenon in terms of a person’s beliefs. Previous theories suggested that when people were in a crowd, they’d lose their independent rational thinking and change their beliefs to conform to the crowd. For example, if say, at the start of a riot, one person in a crowd throws a rock through a window, the beliefs of the people in the crowd would change and they’d act in irrational ways.

But Granovetter believed otherwise. In his view, riots aren’t caused by a collective of people who hold beliefs about what’s right, and then suddenly, because of a mob mentality, change those beliefs. Rather, riots are driven by a social reaction to the behaviour of people in the environment. They are driven by thresholds.

Your threshold is the number of people who have to do an activity, before you join them. You can think of thresholds as a form of peer pressure. The higher your threshold, the more people you need to do something, before you participate.

In the context of a riot, the rebel who needs little encouragement to throw the first rock through a window, has a very low threshold. But, an otherwise law-abiding citizen, who steals a computer, only if everyone around them is also looting, has a very high threshold.

Granovetter formalised these insights as ‘the threshold model of collective behaviour.’ The implications of this is that, regardless of our beliefs, within certain social contexts or thresholds, we could make really bad decisions, even when we know better.

This brings us one step closer to solving the puzzle of Wilt Chamberlain’s irrational decision to switch back to overhand free throw shooting.

Here’s another clue. In Wilt Chamberlain’s autobiography, he wrote “I felt silly, like a sissy, shooting underhanded. I know I was wrong. I know some of the best foul shooters in history shot that way. Even now the best one in the NBA, Rick Barry, shoots underhanded. I just couldn’t do it.” [4]

Did you notice anything strange about Wilt Chamberlain’s comments? Any alarm bells ring based on Granovetter’s threshold model?

Let’s dissect this. First, Chamberlain mentions that “I felt silly, like a sissy.” Why would he feel silly or like a sissy? That’s because almost all basketball players in the NBA at the time, minus Rick Barry, shot overhanded. Plus, the underhand throw was mocked as a ‘granny shot’ for ‘sissies.’ Chamberlain didn’t want to look stupid, in front of his peers and the world.

Second, Wilt Chamberlain said, “I know I was wrong…I just couldn’t do it.” So, despite being completely aware of a good choice, he still made the bad decision to keep shooting overhanded. As predicted within Granovetter’s threshold model, it wasn’t Chamberlain’s beliefs that drove his decision. It was the social context. In other words, Wilt Chamberlain was a high threshold person, who would only stick to the granny shot, if a majority of basketball players also did so. But, what about Rick Barry?

When Barry first switched to underhand free throw shots, as a junior in high school, he also believed that he’d look like a ‘sissy.’ In fact, early on, he was ridiculed for his shooting style. But, Barry didn’t let this discourage him. As far as he was concerned, the only thing that mattered was improving his shots. [5]

Unlike Wilt Chamberlain, Rick Barry had a very low threshold. He didn’t need approval from other people to stick to a good decision that works. And that’s what separates the Wilt Chamberlain’s from the Rick Barry’s of the world.

The Social Courage Decision

We like to think that bad decisions are a result of beliefs or ignorance. But that’s not always true. Most times, we don’t always do what’s best for us, even when we know better, because of peer pressure.

But, there are a handful of people, the Rick Barry’s of the world, who would rather be right, than liked. They have the social courage to put mastery of a task at hand, ahead of social approval.

Unlike the Wilt Chamberlain’s of the world, who die with regrets of what could have been, the Rick Barry’s of the world pass on with no regrets. Because they didn’t let the opinion of others hold them back from being the best person they could’ve been.

Mayo Oshin writes at MayoOshin.com, where he shares practical ideas based on proven science and the habits of highly successful people for a better life. To get strategies on how to stop procrastinating, improve your productivity, decision-making and health, you can join his free weekly newsletter here.

Recent Comments